How sports changed medicine forever

Now and then, a heart-breaking injury on the field or court — or a secret drug problem — does more than stop the game clock.

In his new book, “Tiger Woods’s Back & Tommy John’s Elbow: Injuries & Tragedies that Transformed Careers, Sports, and Society,” Jonathan Gelber, an orthopedic sports medicine surgeon at Olmsted Medical Center in Rochester, Minnesota, examines how momentous medical events in sports reverberate in our larger society — and not always with positive results.

“As a sports-medicine doctor, I wanted to tell stories about injuries in sports. But I wanted to go deeper,” Gelber tells The Post. “And in my research I found that sometimes, there were unintended consequences.”

Here are three high-profile cases that changed the landscape of health care.

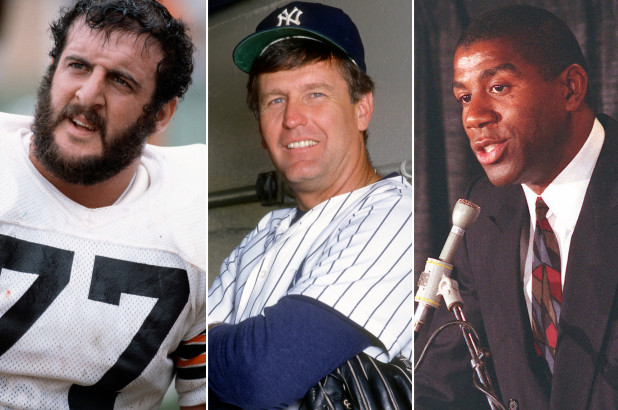

Tommy John’s elbow

Forty-five years ago last week, Dr. Frank Jobe operated on Tommy John, a LA Dodgers baseball pitcher with a bum elbow, using a wrist tendon to repair John’s blown elbow ligament.

No one expected that the groundbreaking procedure would become the norm for pitchers at all levels.

The surgery has allowed pros to extend their careers long past their previous expiration dates dictated by bodily wear and tear — but that’s not necessarily a good thing, says Gelber.

It’s “almost become a crutch to organizations and players,” he says. “It’s easier to send someone to the doctor than to implement league- or club-wide changes” to prevent injury in the first place.

Even more significant: That same procedure, performed on John when he was 31, is now being used to help overworked kids on the ball field by overzealous parents and coaches.

“It’s filtered into the youth ranks and become a right of passage,” Gelber says. Of the Tommy John surgeries done in the US from 2007 to 2011, he notes, 56.8% were performed on teens ages 15 to 19. “It has become too normalized for such a young group of kids.”

Lyle Alzado’s steroids

In the ’90s, there was no more prominent poster boy for the perils of anabolic steroid use than Raiders lineman Lyle Alzado.

For years, the grizzled gridiron star — nicknamed “Three-Mile Lyle” for his nuclear temper — was known for his fearsome play. But when the Super Bowl champion was diagnosed with primary brain lymphoma, a rare brain cancer, in 1991, the football player came clean about his two decades of steroid use.

In a 1991 interview with Sports Illustrated, Alzado attributed his disease to his steroid abuse. The player went on a campaign against performance-enhancing drugs before dying a year later at 43.

But Alzado was a flawed evangelist, Gelber says: It’s unlikely his cancer had anything to do with steroid use.

In fact, he argues, tying the two together buried the real story: The biggest danger of anabolic steroid use is cardiovascular disease. And Gelber believes the mixed messaging cost a lot of lives among steroid users.

“[Alzado] raised awareness, but it also drove the conversation underground,” says Gelber. “Everyone in the bodybuilding community discounted [Alzado’s story]. They saw the steroids worked and no one around them was getting cancer.”

He notes that Alzado’s message fell on deaf ears in the sports world, especially in Major League Baseball, which didn’t start testing for steroids until more than a decade after his death.

Magic Johnson’s diagnosis

On Nov. 7, 1991, Earvin “Magic” Johnson shocked the world when he announced he was HIV positive. At the time, that diagnosis was treated as a death sentence — including socially, to anyone who had it.

“Because of the HIV virus that I have attained, I will have to retire from the Lakers today,” Johnson said in his now-famous press conference. He also stressed that he contracted the disease from a woman (not his wife, Cookie, who was HIV-free and expecting their first child). His announcement spurred many to get tested for HIV and changed the perception of the disease.

At a glance, that’s a good thing. But Gelber found a surprising downside. He says that Johnson’s insistence that he got HIV from a woman attracted the attention of the wrong demographic.

Looking at HIV testing data after Johnson’s announcement, it appears that straight, white men were most affected by his message — that demographic group, Gelber says, was statistically “least likely to have HIV.”

If Cookie had been a bigger part of the narrative, Gelber says, things could have been different. For example, it could have raised HIV awareness for a higher-risk group: straight black women, who “are still a disproportional portion of new diagnoses” today.

“The celebrity effect is real,” says Gelber, but it can miss the mark if the message reaches the wrong people.

Recent Comments